In Fisher’s Hammer horrors, the cross is more than an incidental deterrent - it’s a weapon capable of destroying evil. Religious themes were indeed nearly absent from the silent Nosferatu, but Universal’s 1933 Dracula did include a scene in which Bela Lugosi’s Dracula cringes from an inadvertently displayed crucifix hanging from the neck of a potential victim.įisher’s use of religious imagery, though, went far beyond anything in the Universal films. Not that Fisher was the first filmmaker to depict crosses having power over vampires and other agents of evil. Beginning with his groundbreaking take on Dracula (better known in the US as Horror of Dracula), and above all in his 1968 film The Devil Rides Out ( The Devil’s Bride), Fisher’s films establish the cross as the ultimate spiritual force, a power before which the Devil himself is helpless and powerless, and that can save any who have recourse to it. Leggett’s book goes further, documenting at length that Fisher’s films depict not just the triumph of good over evil, but specifically the triumph of the cross over the powers of hell. Fisher, however, was a high-church Anglican, and famously called his films "basically morality plays" that reflect his personal belief in "the ultimate victory of good over evil." Echoing this, Dracula star Lee cites the ultimate destruction of evil in Fisher’s films as the reason "the Church doesn’t object to these films, and why they are so popular in Ireland, Spain and Italy." Leggett argues that the Universal films were basically areligious, oriented toward science or mythology rather than religion. Fisher’s films were more immediate, less gothic, with a strong sense of internal logic.īut Fisher is most interested in another quality that differentiates Fisher’s films both from the Universal horrors and the later gruesome slasher genre. Earlier horror films and even fantasy films, from silent classics like The Thief of Bagdad and Nosferatu to the Universal Dracula and Frankenstein to The Wizard of Oz, presented fantasy scenarios in a way that was highly stylized. What differentiated Fisher’s films from the earlier Universal oeuvre, besides overt religiosity and more frightening and provocative imagery, was their bracing sense of realism.

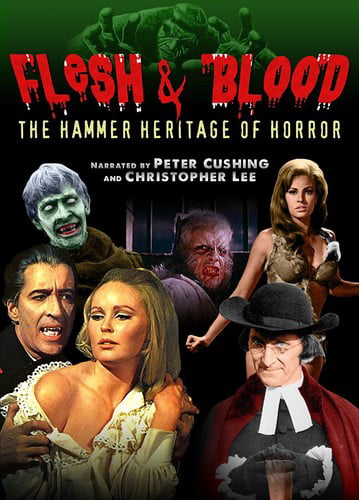

Following on the classic Hollywood Universal horror films of the 1930s and 40s, Fisher pioneered the modern horror film for England’s Hammer Films with remakes of Frankenstein (1957) and Dracula (1958), and went on to direct a number of Hammer staples including Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed and The Devil Rides Out, often working with such Hammer regulars as Christopher Lee ( The Lord of the Rings), Peter Cushing, and Barbara Shelley.

"You don’t say," he chuckled ironically.īy any measure, Fisher is a pivotal figure in the development of the horror genre. When I called Leggett recently to discuss his book and Fisher’s films, and mentioned that I had written a brief essay offering a Christian appraisal of horror, he expressed interest, and laughed appreciatively when I mentioned the reservations some pious viewers have with this genre. He’s a lifelong fan of Fisher, going back to a screening of The Hound of the Baskervilles at the age of 13, and displays a breadth of knowledge about horror and fantasy before and after Fisher and Fisher’s inspirations in classical and ancient mythology as well as biblical and Christian tradition. Leggett’s interest in Fisher and in religious themes in horror films is more than merely professional. Terence Fisher: Horror, Myth and Religion is by Paul Leggett, a Presbyterian clergyman whose New Jersey church happens to be one town over from where I live. The religious themes in the B-movie horror films directed by Terence Fisher for Hammer Films could fill a book. The Cross and the Vampire: Religious Themes in Terence Fisher’s Hammer Horrors SDG

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)